There is a moment of gut-wrenching horror in Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

It begins with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, at the bedside of a fatally wounded German soldier.

“I am resigned to dying soon,” the soldier said to him. “But before that I want to talk about an experience which is torturing me. Otherwise, I cannot die in peace.” Comforted by Wiesenthal’s attention, the soldier began to confess to his role in a barbaric war crime where around two hundred Jewish men, women, and children were marched into a house and burned alive.

“I must tell you of this horrible deed,” cried the soldier. “Tell you because – you are a Jew.”

The soldier begs for the forgiveness that would grant him a peaceful death. His voice quivered, his hand trembled; his exhaustion and remorse were palpable. But Wiesenthal said nothing. He turned and left the soldier without a word.

A day later, he found out the soldier had died, unforgiven.

Perversely cruel as it might seem, the moment haunts Wiesenthal. Was it wrong to withhold forgiveness to the soldier, given he seemed genuinely repentant?

The Sunflower poses an invitation. “Ask yourself a crucial question, ‘what would I have done?’”, Wiestenthal dares the reader.

Wiesenthal tasks philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and genocide survivors with answering the very same question and features their responses throughout the book.

It’s true that many of us will not find ourselves in such a harrowing situation. But some will. Victims of crime can be invited to participate in restorative justice programs where they face the person who has wronged them. One in five Australian women above fifteen years old have been sexually assaulted or threatened – usually by someone they know.

In these cases, a victim may face an ethical dilemma they haven’t chosen. One that feels cruel to subject them to: they must decide whether to grant or withhold forgiveness.

Earning forgiveness

Should we forgive those who have wronged us? What makes someone worthy of forgiveness? Can forgiveness be wrong?

These questions are important for two reasons. First, forgiveness doesn’t always come naturally. At the moment when we’ve been wronged – often severely and traumatically – it’s doubly difficult to meditate on the ethics of forgiveness.

It’s painful, confusing and morally loaded: after all, who wants to be the person who doesn’t forgive when people who do – even when it seems impossible – is held up as a paragon of virtue and humanity?

But second, we need to understand how forgiveness should work because we’re all going to seek forgiveness at some point. We will all wrong someone else at some stage, in big ways or small. If we’ve done some work thinking about how we want to forgive, we’ve got a roadmap to follow when we’re the ones seeking forgiveness.

In Wiesenthal’s case, the genuine remorse shown by the German soldier is what troubles him. He believes the soldier is truly sorry for what he did. Not everyone agrees – was this man remorseful, or was he just scared to die? But whether or not the soldier was remorseful, we tend to agree that remorse matters for forgiveness. If someone is remorseful, we can at least think about forgiving them. If there’s no remorse, it doesn’t seem like a moral challenge to withhold forgiveness.

Genuine remorse

But expressing remorse is hard. It takes more than the non-pologies theologian L. Gregory Jones calls “spinning sorrow”. It involves acknowledging responsibility and wrongdoing. “I’m sorry you were offended” isn’t remorse. It’s performative, and puts the onus on the victim for their own suffering. In short, it says you were offended; I didn’t do anything offensive. Your suffering is on you. That’s not remorse, that’s pig-headedness.

Remorse demands us to understand the full extent of our wrongdoing.

That it was wrong, why it was wrong, and how that wrongdoing has harmed someone else. Which gives us good reason to think that Wiesthenthal’s soldier is not genuinely remorseful.

The horror of the Holocaust depended on the systematic denial of Jewish personhood. They weren’t seen as individuals – people with lives complex, unique, and infinitely valuable. Instead, they were objects to be treated as others saw fit.

By treating Wiesenthal as ‘a Jew’ – a generic placeholder for the actual people the solider murdered – the German soldier is continuing on with the same abhorrent thinking that led to his crimes in the first place. He doesn’t understand the depth of what he did. How can he then apologise in a way that warrants forgiveness?

The politics of forgiveness

To step away from Wiesenthal’s case for a second, how often do we witness apologies that fail to show any awareness of the source of the wrongdoing? On a political level, we see apologies offered by those who continue to benefit from those injustices. Does this constitute remorse, or a genuine understanding of the wrongdoing?

Take political apologies, for instance: some naysayers to Australia’s National Apology to the Stolen Generations argued that the people apologising weren’t the ones who had done anything wrong. The claim here is if we haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t need to be forgiven; and if we don’t need to be forgiven, why would we apologise?

This perhaps misses an important consideration.

If we continue to benefit from a past wrong and fail to address the source of the continued disadvantage, there is a sense in which we’ve prolonged the wrongdoing.

However, it also calls our attention to the role of status in forgiveness. I cannot offer an apology for a wrong I haven’t been involved in.

Equally, I cannot forgive unless I have been wronged, which also complicates the politics of forgiveness: who has the moral authority to forgive? Could Wiesthenthal, who was treated as a ‘generic Jew’ by the soldier, actually forgive – even if he wanted to? After all, the soldier’s crimes did not directly harm him.

Eva Kor was a Holocaust survivor who offered forgiveness to Josef Mengele, doctor of the notorious ‘twin experiments’ in Auschwitz. Her actions brought criticism from other survivors, who said Kor wasn’t entitled to offer forgiveness on behalf of others. Nor should she pressure them to forgive when they were not ready.

Jona Laks, another ‘Mengele twin’, refused to forgive. In Mengele’s case, this is understandable. But what if there was genuine remorse, a commitment to change, and steps to address the wrongdoing? Would it be wrong to refuse forgiveness?

On some occasions, it seems so. For instance, we consider pettiness – when someone is unable to move past very slight or non-existent wrongs – as a vice, or a mark of bad character. I’m not suggesting a Holocaust survivor (or any Jewish person) who refused to forgive the Nazis under any condition was being petty, but this takes us back to the question posed earlier.

Is there anything that’s unforgiveable?

This brings us to the final question: are there some things which are unforgiveable? How should we think about them?

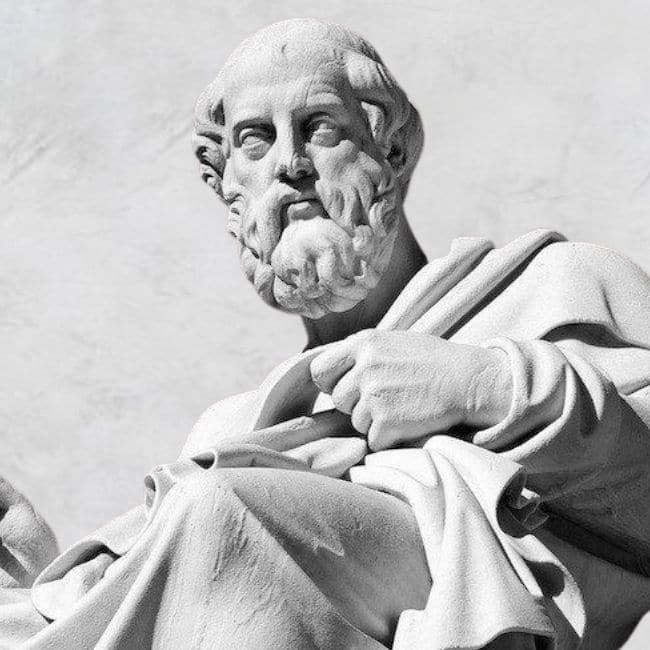

Maybe. Philosopher, Hannah Arendt believed that unforgiveable crimes were those where no punishment could be given that would be proportionate to the crime itself. Where no atonement is possible, no forgiveness is possible. For Arendt, these crimes are an evil beyond redemption.

In contrast, French philosopher Jacques Derrida argued that conditional forgiveness is in fact, not forgiveness. By withholding forgiveness until considerations (like remorse) are met, Derrida believed that we are forgiving someone who is already innocent – that is, someone who no longer needs forgiveness. Only the unremorseful person remains guilty, and only the unremorseful person actually needs forgiveness.

As a result, Derrida concludes with a paradox: only the unforgiveable can be truly forgiven.

Derrida traces his thinking back to religious traditions where forgiveness is unconditional and uneconomic. It is a gift, not a transaction. This is a view L. Gregory Jones believes is centrally important to avoid “weaponising forgiveness”.

I think it’s important to remember that forgiveness should always be a gift and not an expectation. It’s unfair to expect any person who has been victimized, especially if it’s raw, to be ready to forgive.

And — this is particularly important in domestic violence and other kinds of forgiveness — the expectation of forgiveness is also used as a weapon to punish and perpetuate a cycle. It’s often the case in domestic violence, for example, where the abuser will come and say, “you need to forgive me because you’re a Christian” and the person feels obligated to do that. All that does is perpetuate and intensify the violence rather than remedy it.

So how should we think about Wiesenthal’s case? What would we do? It seems quite evident that he had no duty to forgive this Nazi – and that perhaps he had no right to do so. However, if we set aside the question of legitimacy, how might he make this decision?

Some philosophers have argued that self-respect is central to the way we think about forgiveness. Forgiveness involves a recognition that we have value – that we did not deserve to be wronged, and the other person should not have wronged us.

By forgiving, we assert our status in the moral community – our dignity.

However, others might believe such forgiveness reduces their self-worth – especially if this forgiveness leaves the wrongdoer better off than the victim. Forgiveness can grant peace to wrongdoers – as the German soldier knew – but often leaves the victim alone in their trauma.

Author Susan Cheever once wrote that “Being resentful is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die”. For some, this may be true. For others, forgiving might be like giving someone a drink while you are dying of thirst.

Should Wiesenthal have forgiven the soldier? It might all depend on what he could swallow and still look at himself in the mirror.

It may all come down to what he wanted to see when he looked in the mirror.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Big thinker

Relationships