Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard 10 OCT 2015

In the flurry of emotion and analysis that followed the fatal shooting of police accountant Curtis Cheng in Parramatta by 15-year-old Farhad Jabar on 2 October 2015, one fact was more or less overlooked.

A child had been killed.

One of the tragedies of extremism is the way it can make us contemplate or perform acts that ordinarily are unthinkable. The police constable who shot and killed Jabar probably never imagined having to kill a child. And yet on that Friday afternoon, the unthinkable occurred.

Farhad Jabar didn’t seem like your typical kid. He shot a man in cold blood. It’s alleged he was reciting “Allahu Akbar” in the gunfight preceding his death, and a letter containing extremist rantings was reportedly found in his backpack.

We shouldn’t forget the fact of Jabar’s childhood. The police constable who killed him won’t – killing a child is arguably the ultimate moral line in the sand.

But Jabar was a child. At his death he was effectively a child soldier – having allegedly been radicalised by extremist groups in Sydney.

We know how groups abroad use child soldiers, but we’ve rarely been confronted by it directly. We don’t see child soldiers in Australia. The context in this case – extremism, the murder of police staff and allegations of terrorism – made us less sensitive to the fact Jabar was a child.

This insensitivity needn’t be the subject of public cultural haranguing but we shouldn’t forget the fact of Jabar’s childhood. The police constable who killed him won’t – killing a child is arguably the ultimate moral line in the sand.

Even the “American Sniper” Chris Kyle revolted at the idea of killing a child. Although the American Sniper film depicts Bradley Cooper’s Kyle taking the shot, the actual sniper never did so. In his book he writes, “I wasn’t going to kill a kid, innocent or not”.

Jabar was not innocent in any morally relevant sense. His actions meant he had forfeited his right not to be attacked – he had already killed one person and intended to kill several more.

The moral responsibility of the police officers was to neutralise the threat, and it’s reasonable to assume that no less harmful means were available. Killing may well have been the only option.

The constable was innocent of any wrongdoing. It was not the constable’s fault Jabar murdered a man in cold blood. Nor that there were no other means of neutralising him as a threat. In this sense, the constable was duty-bound to shoot Jabar.

But knowing that you’ve done your duty is likely to be cold comfort.

In my experience researching moral psychology among soldiers and veterans, I’ve learned that certain actions “stick” to the psyche more than others. The “stickiest” among them are acts that transgress deeply held moral and cultural norms.

These acts needn’t be crimes, either. Surviving when comrades did not, training accidents and collateral damage can all produce profound moral and psychological distress. In his book What it is Like to Go to War, veteran Karl Marlantes writes:

“Killing someone without splitting oneself from the feelings that the act engenders requires an effort of supreme consciousness that, quite frankly, is beyond most humans.”

How much worse is the killing of a child?

In similarly tragic cases, the military sphere has forms of counselling that aim to do one of two things. They might ignore the moral question altogether and treat this trauma as basic PTSD – Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – which it isn’t. Or they might explain the moral error in judgement – “you think you’ve done something wrong, but you actually haven’t”.

Neither would likely be helpful in a case like this.

Trauma related to the moral character of one’s actions isn’t PTSD in the standard sense. PTSD is about fear for one’s safety. This form of trauma, which I and others refer to as moral injury, is about guilt. Jonathan Shay, the psychiatrist who coined the term, calls this kind of trauma a “soul wound”.

“It’s not your fault” is well intended but – especially when repeated insistently – it can invalidate laudable moral emotions.

Pointing out the error in judgement will probably be equally ineffective. “It’s not your fault” is well intended but – especially when repeated insistently – it can invalidate laudable moral emotions. To feel remorse at having killed a child – even a child soldier like Jabar – is to accurately grasp the tragedy of what has transpired.

Australian philosopher Rai Gaita suggests cases like this reveal the problems with our concept of responsibility. He writes, it is “wrong to say that we should concern ourselves with what we did rather than with the fact that we did it”.

Gaita tells us remorse “is a kind of dying to the world”. We don’t yet know with certainty the best ways to address remorse in therapy, but a likely starting point is for us as a community to recognise the tragedy of what transpired in Parramatta.

A child was killed. And a good person was forced to kill him.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

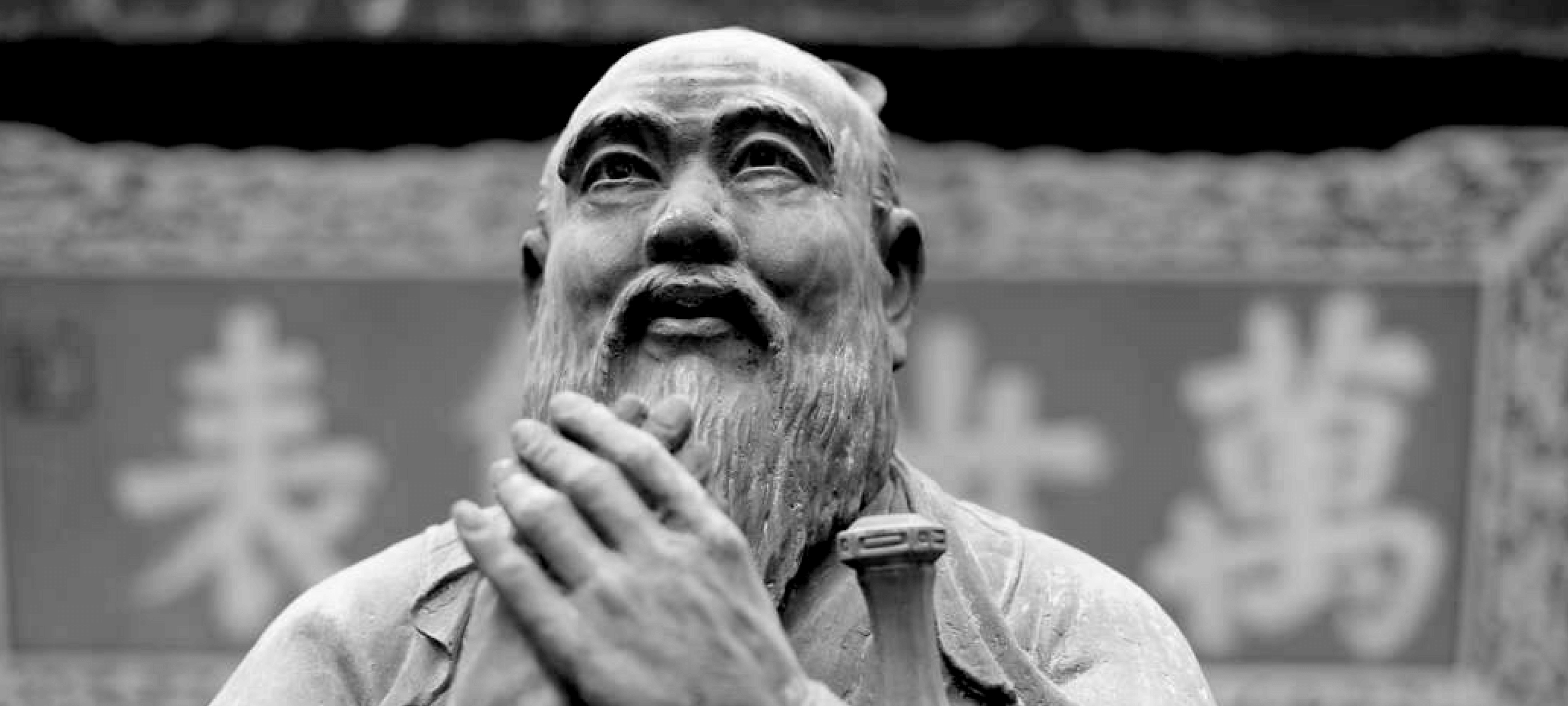

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights