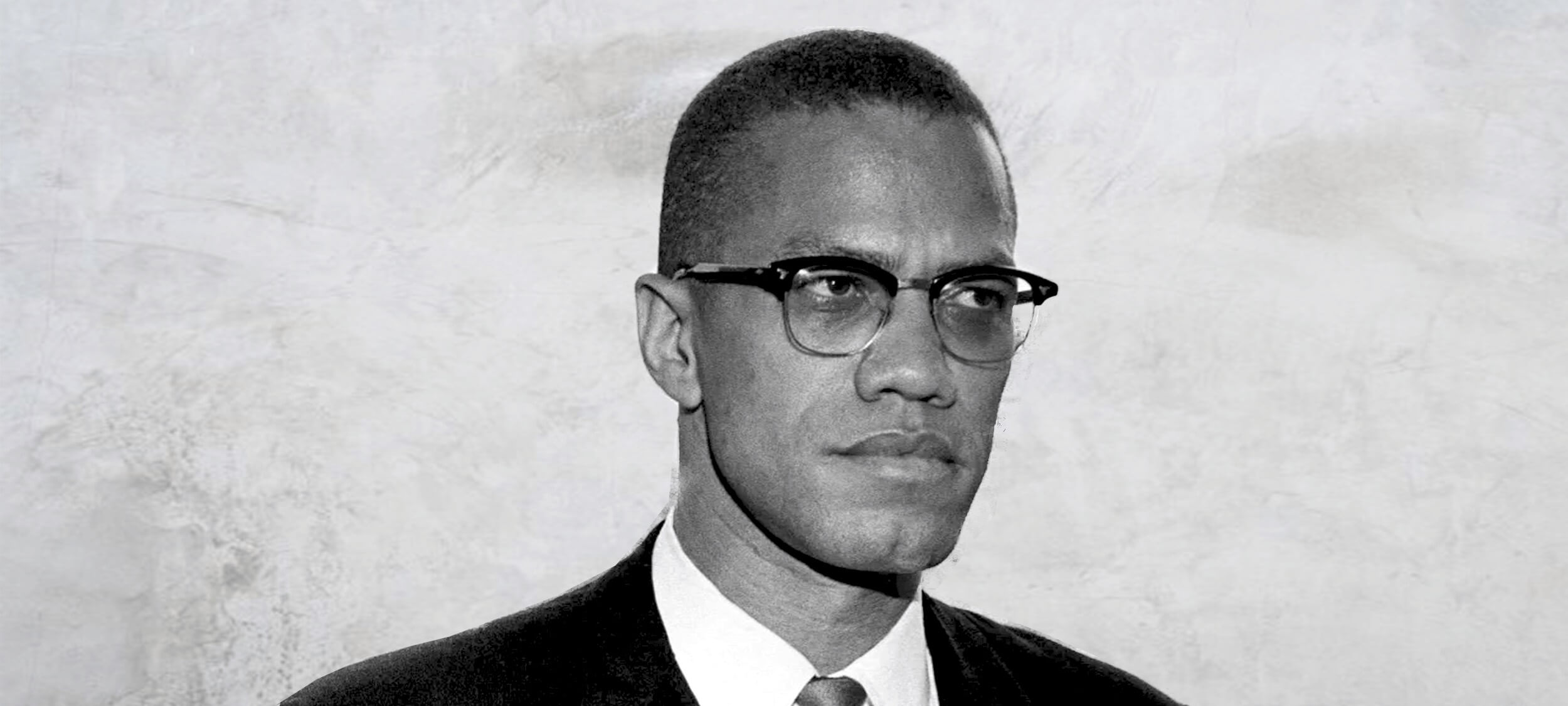

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 7 FEB 2018

Malcolm X (1925—1965) was a Muslim minister and controversial black civil rights activist.

To his admirers, he was a brave speaker of an unpalatable truth white America needed to hear. To his critics, he was a socially divisive advocate of violence. Neither will deny his impact on racial politics.

From tough childhood to influential adult

Malcolm X’s early years informed the man he became. He began life as Malcolm Little in the meatpacking town of Omaha, Nebraska before moving to Lansing, Michigan. Segregation, extreme poverty, incarceration, and violent racial protests were part of everyday life. Even lynchings, which overwhelmingly targeted black people, were still practiced when Malcolm X was born.

Malcolm X lost both parents young and lived in foster care. School, where he excelled, was cut short when he dropped out. He said a white teacher told him practicing law was “no realistic goal for a n*****”.

In the first of his many reinventions, Malcolm Little became Detroit Red, a ginger-haired New York teen hustling on the streets of Harlem. In his autobiography, Malcolm X tells of running bets and smoking weed.

He has been accused of overemphasising these more innocuous misdemeanours and concealing more nefarious crimes, such as serious drug addiction, pimping, gun running, and stealing from the very community he publicly defended.

At 20, Malcolm X landed in prison with a 10 year sentence for burglary. What might’ve been the short end to a tragic childhood became a place of metamorphosis. Detroit Red was nicknamed Satan in prison, for his bad temper, lack of faith, and preference to be alone.

He shrugged off this title and discarded his family name Little after being introduced to the Nation of Islam and its philosophies. It was, he explained, a name given to him by “the white man”. He was introduced to the prison library and he read voraciously. The influential thinker Malcolm X was born.

Upon his release, he became the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and grew its membership from 500 to 30,000 in just over a decade. As David Remnick writes in the New Yorker, Malcolm X was “the most electrifying proponent of black nationalism alive”.

Be black and fight back

Malcolm X’s detractors did not view his idea of black power as racial equality. They saw it as pro-violent, anti-white racism in pursuit of black supremacy. But after his own life experiences and centuries of slavery and atrocities against African and Native Americans, many supported his radical voice as a necessary part of public debate. And debate he did.

Malcolm X strongly disagreed with the non-violent, integrationist approach of fellow civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. The differing philosophies of the two were widely covered in US media. Malcolm X believed neither of King’s strategies could give black people real equality because integration kept whiteness as a standard to aspire to and non-violence denied people the right of self defence. It was this take that earned him the reputation of being an advocate of violence.

“… our motto is ‘by any means necessary’.”

Malcolm X stood for black social and economic independence that you might label segregation. This looked like thriving black neighbourhoods, businesses, schools, hospitals, rehabilitation programs, rifle clubs, and literature. He proposed owning one’s blackness was the first step to real social recovery.

Unlike his peers in the civil rights movement who championed spiritual or moral solutions to racism, Malcolm X argued that wouldn’t cut it. He felt legalised and codified racial discrimination was a tangible problem, requiring structural treatment.

Malcolm X held that the issues currently facing him, his family, and his community could only be understood by studying history. He traced threads between a racist white police officer to the prison industrial complex, to lynching, slavery, and then to European colonisation.

Despite his great respect for books, Malcolm X did not accept them as “truth”. This was important because the lives of black Americans were often hugely different from what was written about – not by – them.

Every Sunday, he walked around his neighbourhood to listen to how his community was going. By coupling those conversations with his study, Malcolm X could refine and draw causes for grievances black people had long accepted – or learned to ignore.

We are human after all

Dissatisfied with their leader, Malcolm X split from the Nation of Islam (who would go on to assassinate him). This marked another transformation. He became the first reported black American to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his final renaming, he returned to the US as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

On his pilgrimage, he had spoken with Middle Eastern and African leaders, and according to his ‘Letter from Mecca’ (also referred to as the ‘Letter from Hajj’), began to reappraise “the white man”.

Malcolm X met white men who “were more genuinely brotherly than anyone else had ever been”. He began to understand “whiteness” to be less about colour, and more about attitudes of oppressive supremacy. He began to see colonialist parallels between his home country and those he visited in the Middle East and Africa.

Malcolm X believed there was no difference between the black man’s struggle for dignity in America and the struggle for independence from Britain in Ghana. Towards the end of his life, he spoke of the struggle for black civil rights as a struggle for human rights.

This move from civil to human rights was more than semantics. It made the issue international. Malcolm X sought to transcend the US government and directly appeal to the United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead.

In a way, Malcolm X was promoting a form of globalisation, where the individual, rather than the nation, was on centre stage. Oppressed people took back their agency to define what equality meant, instead of governments and courts. And in doing so, he linked social revolution to human rights.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights