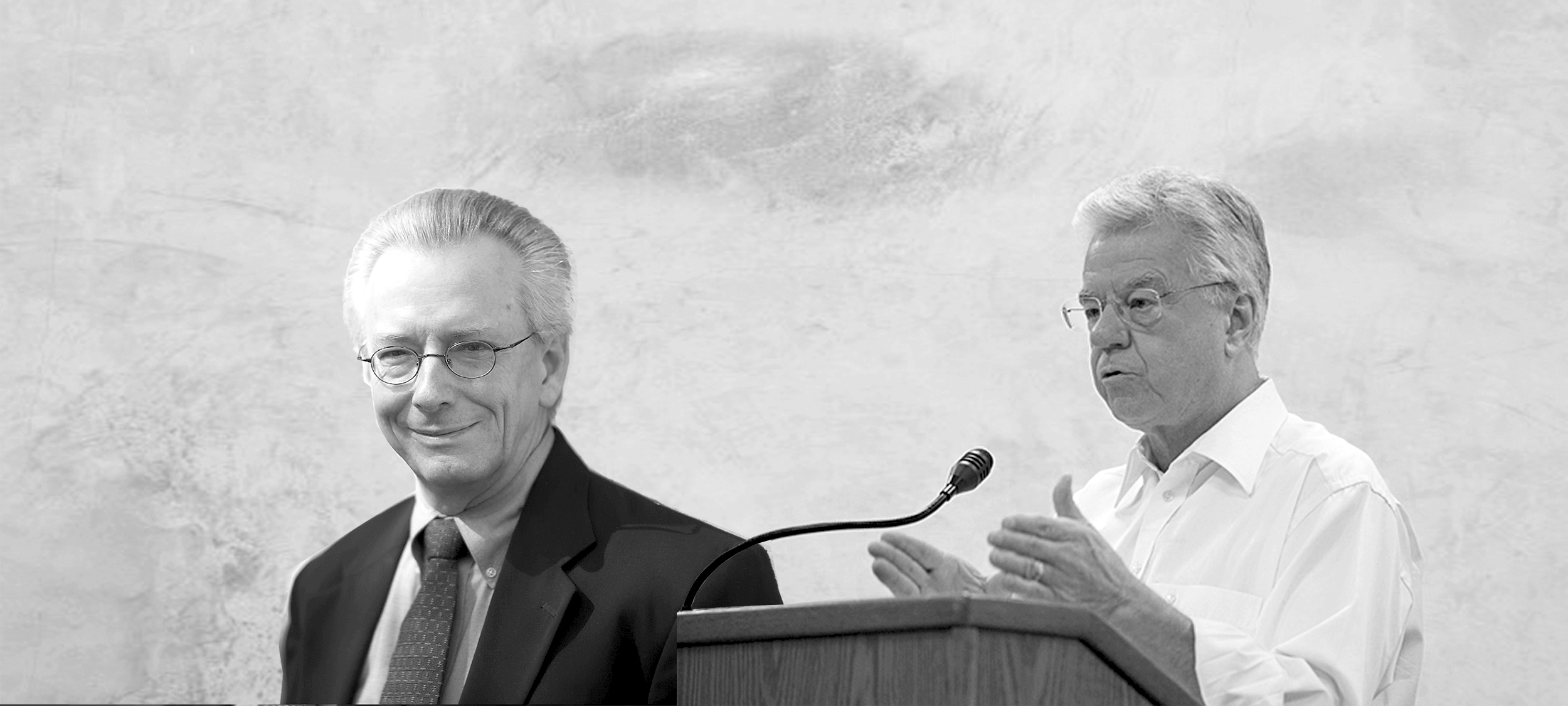

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 1 DEC 2017

Thomas L Beauchamp (1939—present) and James F Childress (1940—present) are American philosophers, best known for their work in medical ethics. Their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics was first published in 1985, where it quickly became a must read for medical students, researchers, and academics.

Written in the wake of some horrific biomedical experiments – most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of rural black men, their partners, and subsequent children were infected or died from treatable syphilis – Principles of Biomedical Ethics aimed to identify healthcare’s “common morality”. These are its four principles:

- Respect for autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

These principles are often in tension with one another, but all healthcare workers and researchers need to factor each into their reflections on what to do in a situation.

Respect for autonomy

Philosophers usually talk about autonomy as a fact of human existence. We are responsible for what we do and ultimately any action we take is the product of our own choice. Recognising this basic freedom at the heart of humanity is a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress.

By itself, the idea human beings are free and in control of themselves isn’t especially interesting. But in a healthcare setting, where patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy for a patient’s autonomous decision to be disrespected.

Beauchamp and Childress were writing at a time when the expertise of doctors meant they often took extreme measures in doing what they had decided was in the best interests of their patient. They adopted a paternalistic approach, treating their patients like uninformed children rather than autonomous, capable adults. This went as far as performing involuntary sterilisations. In one widely discussed court case in bioethics, Madrigal v Quillian, ten Latina women in the US successfully sued after doctors performed hysterectomies on them without their informed consent.

Legally speaking, the women in Madrigal v Quillian had provided consent. However, Beauchamp and Childress explain clearly why the kind of consent they provided isn’t adequate. The women – who spoke Spanish as a first language – were all being given emergency caesareans. They were asked to sign consent forms written in English which empowered doctors to do what they deemed medically necessary.

In doing so, they weren’t being given the ability to exercise their autonomy. The consent they provided was essentially meaningless.

To address this issue, Beauchamp and Childress encourage us to think about autonomy as creating both ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ duties. The negative duty influences what we must not do: “autonomous actions should not be subject to controlling constraints by others”, they write. But positively, autonomy also requires “respectful treatment in disclosing information” so people can make their own decisions.

Respecting autonomy isn’t just about waiting for someone to give you the OK. It’s about empowering their decision making so you’re confident they’re as free as possible under the circumstances.

Nonmaleficence: ‘first do no harm’

The origins of medical ethics lie in the Hippocratic Oath, which although it includes a lot of different ideas, is often condensed to ‘first do no harm’. This principle, which captures what Beauchamp and Childress mean by non-maleficence, seems sensible on one level and almost impossible to do in practice on another.

Medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Surgeons cut people open, doctors write prescriptions for medicines with a range of side effects, researchers give sick people experimental drugs – the list goes on. If the first thing you did in medicine was to do no harm, it’s hard to see what you might do second.

This is clearly too broad a definition of harm to be useful. Instead, Beauchamp and Childress provide some helpful nuance, suggesting in practice, ‘first do no harm’ means avoiding anything which is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful. All medicine has some risk. The relevant question is whether the level of harm is proportionate to the good it might achieve and whether there are other procedures that might achieve the same result without causing as much harm.

Beneficence: do as much good as you can

Some people have suggested Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles are three principles. They suggest beneficence and non-maleficence are two sides of the same coin.

Beneficence refers to acts of kindness, charity and altruism. A beneficent person does more than the bare minimum. In a medical context, this means not only ensuring you don’t treat a patient badly but ensuring you treat them well.

The applications of beneficence in healthcare are wide reaching. On an individual level, beneficence will require doctors to be compassionate, empathetic and sensitive in their ‘bedside manner’. On a larger level, beneficence can determine how a national health system approaches a problem like organ donation – making it an ‘opt out’ instead of ‘opt in’ system.

The principle of beneficence can often clash with the principle of autonomy. If a patient hasn’t consented to a procedure which could be in their best interests, what should a doctor do?

Beauchamp and Childress think autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances: when there is risk of serious and preventable harm, the benefits of a procedure outweigh the risks and the path of action empowers autonomy as much as possible whilst still administering treatment.

However, given the administration of medical procedures without consent can result in legal charges of assault or battery in Australia, there is clearly still debate around how to best balance these two principles.

Justice: distribute health resources fairly

Healthcare often operates with limited resources. As much as we would like to treat everyone, sometimes there aren’t enough beds, doctors, nurses or medications to go around. Justice is the principle that helps us determine who gets priority in these cases.

However, rather than providing their own theory, Beauchamp and Childress pointed out the various different philosophical theories of justice in circulation. They observe how resources are distributed will depend on which theory of justice a society subscribes to.

For example, a consequentialist approach to justice will distribute resources in the way that generates the best outcomes or most happiness. This might mean leaving an elderly patient with no dependents to die in order to save a parent with young children.

By contrast, they suggest someone like John Rawls would want the access to health resources to be allocated according to principles every person could agree to. This might suggest we allocate resources on the basis of who needs treatment the most, which is the way paramedics and emergency workers think when performing triage.

Beauchamp and Childress’s treatment of justice highlights one of the major criticisms of their work: it isn’t precise enough to help people decide what to do. If somebody wants to work out how to distribute resources, they might not want to be shown several theories to choose between. They want to be given a framework for answering the question. Of course when it comes to life and death decisions, there are no easy answers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Libertarianism and the limits of freedom

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships