Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 19 FEB 2018

Uncannily specific ads target you every single day. With the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’, you get a peek at the algorithm that decides it. Oscar Schwartz explains why that’s more complicated than it sounds.

If you’re an EU resident, you will now be entitled to ask Netflix how the algorithm decided to recommend you The Crown instead of Stranger Things. Or, more significantly, you will be able to question the logic behind why a money lending algorithm denied you credit for a home loan.

This is because of a new regulation known as “the right to an explanation”. Part of the General Data Protection Regulation that has come into effect in May 2018, this regulation states users are entitled to ask for an explanation about how algorithms make decisions. This way, they can challenge the decision made or make an informed choice to opt out.

Supporters of this regulation argue that it will foster transparency and accountability in the way companies use AI. Detractors argue the regulation misunderstands how cutting-edge automated decision making works and is likely to hold back technological progress. Specifically, some have argued the right to an explanation is incompatible with machine learning, as the complexity of this technology makes it very difficult to explain precisely how the algorithms do what they do.

As such, there is an emerging tension between the right to an explanation and useful applications of machine learning techniques. This tension suggests a deeper ethical question: Is the right to understand how complex technology works more important than the potential benefits of inherently inexplicable algorithms? Would it be justifiable to curtail research and development in, say, cancer detecting software if we couldn’t provide a coherent explanation for how the algorithm operates?

The limits of human comprehension

This negotiation between the limits of human understanding and technological progress has been present since the first decades of AI research. In 1958, Hannah Arendt was thinking about intelligent machines and came to the conclusion that the limits of what can be understood in language might, in fact, provide a useful moral limit for what our technology should do.

In the prologue to The Human Condition she argues that modern science and technology has become so complex that its “truths” can no longer be spoken of coherently. “We do not yet know whether this situation is final,” she writes, “but it could be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do”.

Arendt feared that if we gave up our capacity to comprehend technology, we would become “thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible, no matter how murderous it is”.

While pioneering AI researcher Joseph Weizenbaum agreed with Arendt that technology requires moral limitation, he felt that she didn’t take her argument far enough. In his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason, he argues that even if we are given explanations of how technology works, seemingly intelligent yet simple software can still create “powerful delusional thinking in otherwise normal people”. He learnt this first hand after creating an algorithm called ELIZA, which was programmed to work like a therapist.

While ELIZA was a simple program, Weizenbaum found that people willingly created emotional bonds with the machine. In fact, even when he explained the limited ways in which the algorithm worked, people still maintained that it had understood them on an emotional level. This led Weizenbaum to suggest that simply explaining how technology works is not enough of a limitation on AI. In the end, he argued that when a decision requires human judgement, machines ought not be deferred to.

While Weizenbuam spent the rest of his career highlighting the dangers of AI, many of his peers and colleagues believed that his humanist moralism would lead to repressive limitations on scientific freedom and progress. For instance, John McCarthy, another pioneer of AI research, reviewed Weizenbaum’s book, and countered it by suggesting overregulating technological developments goes against the spirit of pure science. Regulation of innovation and scientific freedom, McCarthy adds, is usually only achieved “in an atmosphere that combines public hysteria and bureaucratic power”.

Where we are now

Decades have passed since these first debates about human understanding and computer power took place. We are only now starting to see them breach the realms of philosophy and play out in the real world. AI is being rolled out in more and more high stakes domains as you read. Of course, our modern world is filled with complex systems that we do not fully understand. Do you know exactly how the plumbing, electricity, or waste disposal that you rely on works? We have become used to depending on systems and technology that we do not yet understand.

But if you wanted to, you could come to understand many of these systems and technologies by speaking to experts. You could invite an electrician over to your home tomorrow and ask them to explain how the lights turn on.

Yet, the complex workings of machine learning means that in the near future, this might no longer be the case. It might be possible to have a TV show recommended to you or your essay marked by a computer and for there to be no-one, not even the creator of the algorithm, to explain precisely why or how things happened the way they happened.

The European Union have taken a moral stance against this vision of the future. In so doing, they have aligned themselves, morally speaking, with Hannah Arendt, enshrining a law that makes the limited scope of our “earth-bound” comprehension a limit for technological progress.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

We are turning into subscription slaves

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

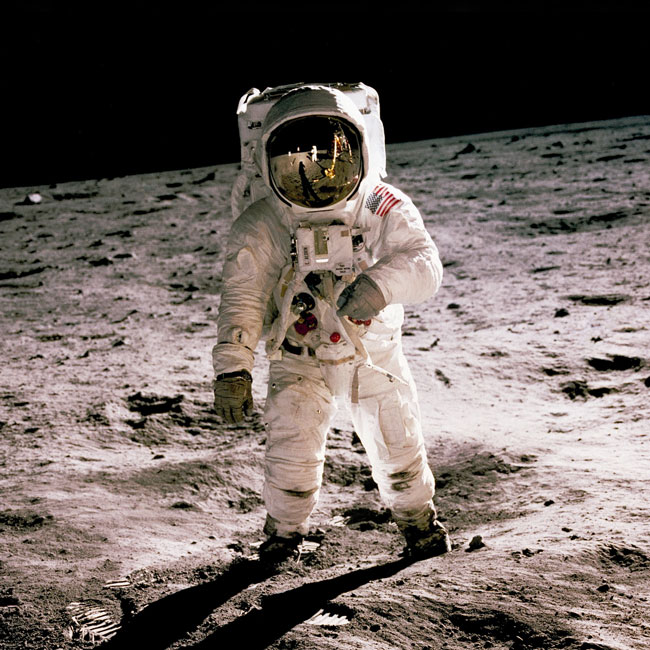

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology